Increasingly the management of interest rate swaps is becoming a requirement for corporates, governments and anyone managing debt. This interest rate swap tutorial is designed to give you a baseline understanding of interest rate swaps and how they work – including valuations and reporting with specific reference to LIBOR and SONIA for those in the UK. It is based on our Interest Rate Swaps eBook which you can also download for reference – it includes the following content plus some more technical detail in the Appendix.

Why we need an interest rate swap tutorial

The interest rate swap market is too big to fathom. According to the Bank for International Settlements in 2014 interest rate swaps were the largest component of the global OTC derivative market, representing 60%, with the notional amount outstanding in OTC interest rate swaps of $381 trillion. That’s a big number. Despite the increased regulatory environment and scrutiny derivatives, including interest rate swaps, received post the 2008 Global Financial Crisis these instruments are a fundamental underpinning of the financial system. (Interested in the history? We have developed a brief overview stretching back to 1981.)

The most common type of swap is a plain vanilla interest rate swap and is when one party exchanges its fixed rate obligation with a second party’s floating rate obligation in the same currency. Currency swaps, sometimes referred to as cross-currency swaps, are also very common, especially in the realm of international financing. A cross-currency interest rate swaps involve exchanging cashflows in different currencies.

In Hedgebook we have over $5 billion of (primarily borrower) interest rate swaps recorded. This is a mix of corporates using these instruments to hedge the interest rate risk associated with debt, plus auditor clients who use Hedgebook to independently value interest rate swaps during their audit engagements.

Introduction to interest rate swaps

Interest rate swaps (or IRSs) are often simply described as an exchange of cash flows. For example, one counterparty to the transaction pays on a fixed interest rate basis and receives on a floating rate basis and vice versa for the other counterparty. The reason is to hedge interest rate risk.

The clearest way to understand an IRS is by way of an example so let’s use a borrower who wishes to fix their interest rate exposure and protect against a rise in interest rates. Many of us borrow money from the bank in the form of a mortgage for our home and we choose to lock in the certainty of the interest rate payments by fixing the interest rate for a few years. A pretty simple concept.

For corporate borrowers

The corporate borrower has a few more options available to them to achieve certainty over interest costs on borrowings. They can borrow on a fixed rate basis similar to our residential mortgages. Alternatively, they could borrow from the bank on a floating rate basis and then enter a pay fixed interest rate swap to lock in the interest rate. The outcome is the same.

The corporate borrower has a few more options available to them to achieve certainty over interest costs on borrowings. They can borrow on a fixed rate basis similar to our residential mortgages. Alternatively, they could borrow from the bank on a floating rate basis and then enter a pay fixed interest rate swap to lock in the interest rate. The outcome is the same.

However, the advantage of the IRS is the flexibility it allows the borrower in regards to the term you can fix and the flexibility to restructure. It is common for a borrower to fix through the IRS market out to ten years or longer. It is much harder, and more expensive, to get the bank to fix interest rates long term. Banks need to be compensated for tying up capital for such an extended period of time.

It is also much harder, and expensive, to break debt that has been borrowed on a fixed rate basis. Comparatively, restructuring an IRS is a straightforward process. It also allows the corporate borrower to take advantage of prevailing interest rate market opportunities or “play the yield curve” to use financial market parlance.

If a fixed rate is swapped for a floating rate, a rise in interest rates over the contract life could result in higher debt servicing costs.

If a floating rate is swapped for a fixed rate, the reverse can be said: while the party with the fixed rate is protected from interest rate volatility, it misses out on the opportunity to benefit from the shifting rate environment. We go into this in a little more detail in this article exploring ‘just what is an interest rate swap’.

Terminology commonly used with Interest Rate Swaps

In this interest rate swap tutorial it is important to understand the terms that are commonly used. The components of a typical interest rate swap would be defined in the swap confirmation which is a document that is used to contractually outline the agreement between the two parties. The components defined in this agreement would be:

NOTIONAL

The fixed and floating coupons are paid out based on what is known as the notional principal or just notional. If you were hedging a loan with £1 million principal with a swap, then the swap would have a notional of £1 million as well. Generally, the notional is not exchanged and is only used for calculating cashflow amounts.

FIXED RATE

This is the interest rate that will be used to calculate payments made by the fixed payer. This stream of payments is known as the fixed leg of the swap.

COUPON FREQUENCY

This is how often coupons would be exchanged between the two parties, common frequencies are annual, semi-annual, quarterly and monthly. In a vanilla swap the floating and fixed coupons would have the same frequency but it is possible for the cashflows to have different frequencies.

BUSINESS DAY CONVENTION

This defines how coupon dates are adjusted for weekends and holidays. Typical conventions are Following Business Day and Modified Following.

FLOATING INDEX

This defines which index is used for setting the floating coupons. Historically, the most common index has been LIBOR but this has recently been replaced with Risk Free Rates such as SONIA in the UK.

DAY COUNT CONVENTIONS

These are used for calculating the portions of the year when calculating coupon amounts. We explore these in more detail in the Appendix.

So – how do interest rate swaps work?

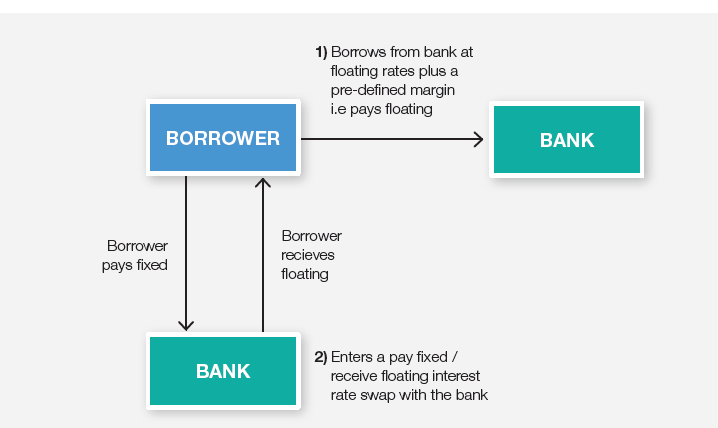

Explaining how an IRS (or Interest Rate Swap) works require us to understand the concept of exchanging cashflows. The diagram below represents the cash flows associated with a borrower using an IRS to fix interest costs:

One: The company borrows money from the bank, say £10 million for our example, on a floating rate basis.

- There are floating-rate benchmarks for different currencies i.e. SONIA in the UK, BBSW in Australia, BKBM in NZ, EURIBOR in Europe etc., which changes/sets every day.

- The bank will charge a margin on the money it lends e.g. 2% The effect for the company is it borrows money at a floating rate + 2%

Two: The company wishes to fix the interest cost.

- To achieve this, it enters a pay fixed/receive floating IRS with a bank (maybe the same bank as it has borrowed from, but not necessarily).

- Assuming the company wishes to fix the entire £10 million i.e. the swap is entered for £10 million.

It could just as easily decide to fix only half the amount i.e. £5 million. This is where you see some of the flexibility an IRS allows the company when considering its interest rate risk management profile.

Under the terms of the pay fixed swap, the borrower will pay the bank a fixed interest rate and receive floating interest from the bank i.e. exchange of cashflows. Note: there is no exchange of principal, only interest.

The floating rate received through the swap offsets the floating rate paid to the bank for the debt. The net impact to the borrower is paying a fixed rate (through the swap) plus the margin the bank charges for borrowing the money (2%).

Factors to consider when using interest rate swaps to hedge debt

Firstly, the roll-dates of the IRS should match that of the debt. That means, if the floating rate on the debt sets every three months, then so should the floating rate on the IRS, and on the same day.

The underlying reference rate on the debt and the swap should also match i.e., SONIA, BKBM, BBSW, EURIBOR, etc. Aligning the date and rate-set ensures there is no “basis risk” within the hedge. It also ensures it passes muster from a hedge accounting perspective if it is designated into a hedge relationship.

The example above is designed to provide a basic understanding of the concept of an IRS. We have used the floating rate borrower as an example. However, interest rate swaps are used by an array of market participants for a multitude of reasons. This includes investors wishing to structure their income profiles or borrowers who have borrowed on a fixed term but wish to have exposure to floating interest rates.

Valuations and the cashflow map

The value of an interest rate swap changes constantly depending on the financial markets outlook for interest rates. On the first day of executing an IRS the valuation will be close to zero as the fixed rate of the swap will be the equivalent of the market rate for the specific parameters of the transaction. Thereafter, the valuation will go up or down based on the market. To understand how the valuation is derived requires netting off the cashflows of the fixed versus floating legs of the swap.

Using the most prevalent type of IRS we see in Hedgebook as an example (a pay fixed swap), it is the net of the pay fixed and receive floating cashflows discounted to net present value (NPV) that derives the valuation.

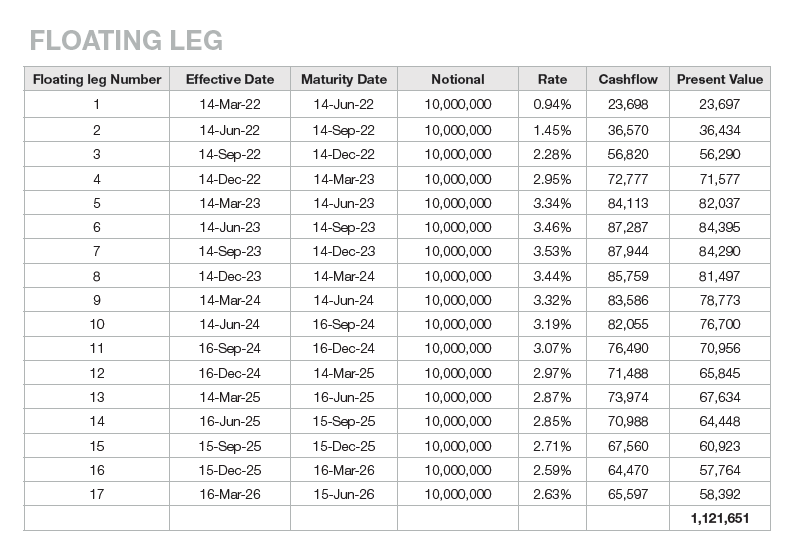

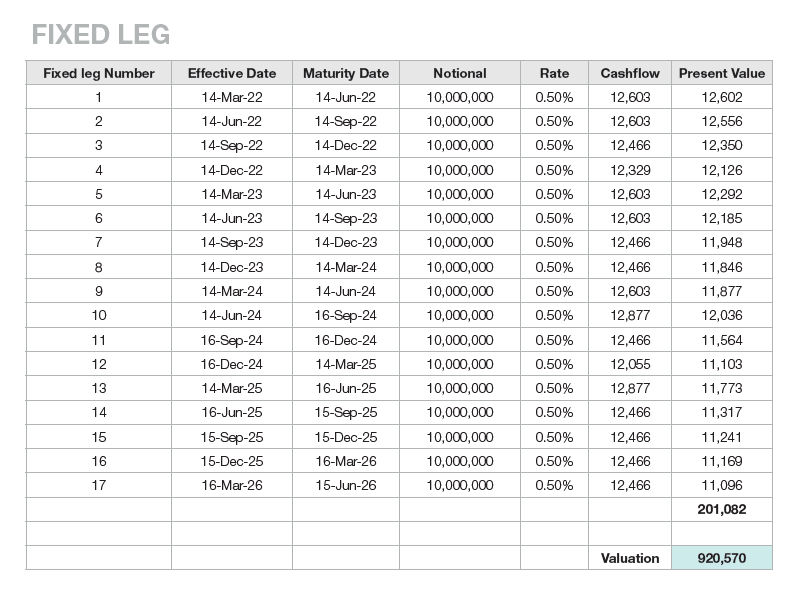

In the following example we are using an IRS that was transacted in 2022 using the relevant interest rates for that time.

Transaction details:

Notional = £10 million

Pay Fixed Rate = 0.50%

Effective Date = 14 June 2021

Maturity Date = 14 June 2026

Frequency = Quarterly/Quarterly

Floating Index = SONIA

When we value this interest rate swap today (13 June 2022) the valuation is +£920k. It is intuitive that the valuation (aka mark-to-market) is positive as the transaction was entered 12 months ago in a much lower interest rate environment. The derivative has benefited from the subsequent increase in UK interest rates. Paying a 0.50% fixed rate for five years was a great decision. To see the breakdown of the +£920k valuation we can look at the individual legs of the swap:

The SONIA interest rate curve is used to:

• Imply the future floating rates for the floating leg of the swap

• Discount the cashflows back to present value

The net of the pay fixed cashflows (£201,082) and the receive floating cashflows (£1,121,651) result in the +£920k valuation.

LIBOR cessation and the impact on valuations

Note: This is BIG if you’re in the UK

Up to 31 December 2021 the primary index for the floating leg of GBP and USD interest rate swaps was LIBOR. Following the cessation of LIBOR, the index is SONIA for GBP and SOFR for USD. This has created some confusion when it comes to valuations which we have witnessed with the queries we have fielded from our auditor users.

When valuing a GBP interest rate swap at a Valuation Date beyond 31 Dec 21, it is important to use the SONIA zero curve as there is a material difference for the implied future floating legs and discount factors between a LIBOR and SONIA curve. If a swap is valued using the LIBOR curve but is compared to a third-party valuation e.g., a bank valuation, the valuations will likely not align.

Worth noting is that if a swap has not been redocumented as SONIA based, the floating leg of the swap needs to have a margin of 27.66bp added to it. The 27.66bp spread has been pre-set as the official fallback spread as outlined here.

FINANCIAL REPORTING REQUIREMENTS

For users of interest rate swaps there are reporting requirements for financial instruments. Many companies try to complete the necessary compliance through using spreadsheets and bank valuations which is not only poor practice (valuations should be independent) but also error prone and time consuming. Hedgebook streamlines, simplifies and improves the ever-increasing burden of year-end reporting requirements. When considering interest rate swaps there are four key reporting requirements to consider:

1. Fair value (IFRS 13 / AASB 13)

IFRS 13 clearly states that valuations need to be an independent “exit price” for the transaction. It is hard to argue that a valuation from one of the counterparties to the transaction (i.e. the bank), constitutes an independent valuation, however, there are still many companies that rely on their bank for this information.

Such reliance on the bank is understandable when the auditor accepts this approach, although we are seeing a much bigger push by the audit community to challenge companies on the lack of independence of a bank valuation given the bank is counterparty and valuer of the financial instrument. Historically there have been few economic alternatives to bank valuations, that is no longer a valid argument.

2. CVA/DVA (IFRS 13 / AASB 13)

The most recent compliance requirement for companies using financial instruments is the adjustment to fair value for credit. IFRS 13 requires a Credit Value Adjustment (CVA) or Debit Value Adjustment (DVA) to all financial instruments.

Financial institutions have been credit adjusting their own positions for years, however, the requirement has filtered down so that all parties to financial instrument transactions must calculate and apply a credit adjustment.

There is a strong argument that it is overkill for companies using financial instruments to hedge their foreign exchange cashflows (payments/receipts) or debt using plain vanilla instruments to have to make CVA/DVA adjustments.

There is little added-value to the company, there is a cost to calculate the adjustment and the number is often immaterial (the number still has to be calculated to determine whether it’s immaterial or not, however).

It is different if you are trading financial instruments or are using credit hungry instruments such as cross-currency interest rate swaps but auditors, as prescribed by the accounting standards, are (or should be) forcing all financial instruments to be adjusted by CVA/DVA.

There is a multitude of approaches to calculating CVA/DVA from the complex (potential future exposure method) to the simple (current exposure method). For those using plain vanilla instruments such as FX forwards or interest rate swaps then a simple methodology is appropriate.

3. Sensitivity analysis (IFRS 7)

As part of the notes to the accounts under IFRS 7 there is a requirement to include a sensitivity analysis for financial instruments. This is a “what if” scenario that requires the re-calculation of fair value if the underlying market data is flexed.

Often a +/-100bp parallel shift in the yield curve for interest rate instruments is applied. In theory there should be some sense check applied to the probability of the movement occurring i.e., if interest rates are close to zero then there is a low probability of a -100 basis point adjustment in the curve.

4. Hedge effectiveness testing (IAS 39 / IFRS 9 / AASB 9)

One of the biggest headaches at year-end is for those hedge accounting. Hedge accounting was introduced for practical reasons – remove noisy P&L volatility from unrealised gains/losses on financial instruments and put these adjustments on the balance sheet instead. In the early days of hedge accounting the approach was complicated and expensive.

As auditors and accountants understanding of hedge accounting has developed over time, the process of hedge accounting has become much less complex. The most important aspect is the documentation. The effectiveness testing aspect of hedge accounting is fairly straightforward, particularly when utilising a treasury management system.

Interest rate swap tutorial – in summary

Interest rate swaps are a widely used financial instrument but can seem complex. We have attempted to bring some clarity through explaining what they are, how they work and how they are valued.

Interest rate swaps are a widely used financial instrument but can seem complex. We have attempted to bring some clarity through explaining what they are, how they work and how they are valued.

Capturing a swap in Hedgebook is a simple process, with the entry of all of the key parameters in a single deal input screen. The face value, maturity date, reset frequency accrual basis and coupon rate and coupon margins are entered and the swap is saved.

Fair value (mark-to-market) calculations for interest rate swaps plus the additional reporting requirements remove the manual elements of complying with accounting standards such as IFRS 13 and IFRS 7, and remove the reliance on banks for fair values.

Next steps

If you would like a copy of this content please download our Interest Rate Swaps for Smart People eBook. It also includes a technical appendix for those who are interested in the math behind this.

If you’ve discovered managing interest rate swaps is something you need to take a closer look at (or want to manage better) we should probably have a chat. Hedgebook is an easy-to-use specialist treasury management solution that helps you manage interest rate swaps and FX hedging. It’s cloud-based and has a global following. But don’t take our word for it – let us show you how it works. You can schedule a call here – demos typically take 15-20 mins plus QnA. We look forward to continuing to help you on your Interest Rate Swap journey.